Fiborn Quarry history

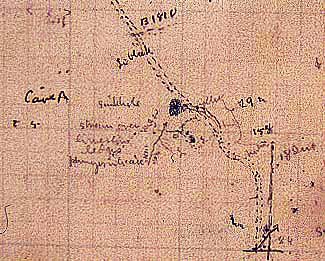

The quarry works in 1924, including the locomotive sheds at left, the sorter and loader house in the center, and locomtives, at right, which hauled ore-filled cars to the main rail line north of the quarry.

A steam shovel collects rock broken up by blasting to load into ore cars.

Quarry workers on a "dinky" locomotive, which hauled cars of broken rock to the crusher.

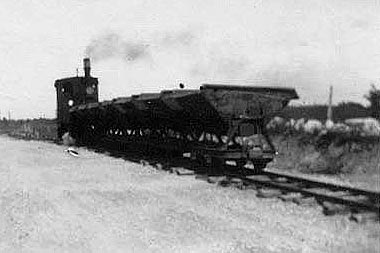

A dinky locomotive pulls ore cars filled with limestone.

Quarry workers outside the machine shop.

Quarry workers walk to the boarding house, which along with housing single male workers, served as a social center, hosting occasional square dances, traveling salesman and church services.

Children play near the school house.

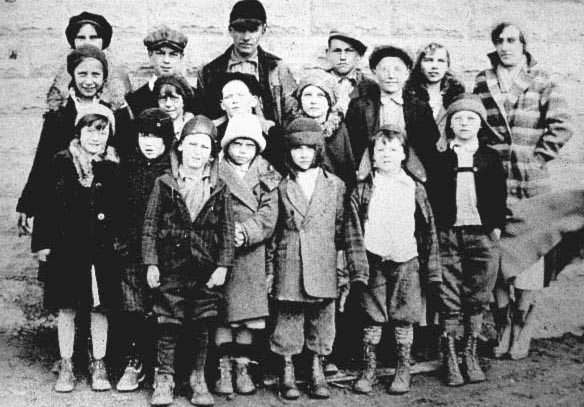

Emma Kalnbach (far right) the Fiborn school's last teacher, with one of her classes in the 1930s.

The unusually pure limestone found in what is now the Fiborn Karst Preserve led to development of Fiborn Quarry, which operated from early 1905 until January 1936. The quarry mined, crushed and shipped limestone for use mostly in steelmaking, but also calcium carbide manufacturing and road building.

A small town grew up next to the quarry, which included an elementary school, a boarding house, a company store and housing for employees and their families.

“You just felt like you were living in a little world all of your own. Just like there was no other place," recalled one former resident who was 13 years old in 1930. “You had your grocery store. You had your post office. You had your school. You had your minister that came in there and gave services. And it just seemed like it was real private.”

Workers broke up the limestone with dynamite, steam shovels loaded the rock into cars which hauled it to a crusher. Crushed limestone was sorted into different sizes hauled on the railroad spur 3-4 miles north to Fiborn Junction and the main rail line to Sault Ste. Marie.

At first, the quarry supplied several industries in the region. After founders William Fitch and and Chase Osborn sold the property to Algoma Steel Corp. in late 1909, Fiborn supplied the Canadian steelmaker almost exclusively, and its production ups and downs over the years tracked Algoma’s own output. Demand and output grew steadily through the World War I years, only to crash after the war. The quarry was closed for extended periods from 1921 to ’23, then enjoyed steady production and an active village life until the Great Depression began to take its toll in 1930. The quarry operated enough to sustain the village school until 1933 or ’34, was idled for much of 1935, then briefly started in January 1936 before being permanently closed. Algoma Steel was able to get high-quality limestone from Rogers City shipped much cheaper by boat. That, combined with expensive repairs and upgrades needed at Fiborn, spelled the end of the quarry and the village that grew up around it.

When the quarry first opened, the South Shore rail line was the only transportation available. Roads began to allow cars to travel in the area by 1914, and a road to Fiborn was completed in 1916 or ’17.

Few families lived at Fiborn in its early years, based on the 1910 census. Most workers stayed at the company boarding house, even some men who were married but apparently living at the quarry without their families. The workforce was a mix of Michigan natives of several ethnic strains, a scattering of men from Ohio, Indiana, Pennsylvania and New York, and immigrants from Canada, Finland, Bulgaria, Sweden, the British Isles and France. Italian immigrants joined the mix in the 1920s and ‘30s. The boarding house employed a housekeeper, cook, waitress and two dishwashers – all women. One was from Indiana, the others immigrants from Finland, Sweden and England. Two had children, and apparently no husband living with them, though both were listed as married for 13 years or more, and both reported having more children than those living with them.

Over the years, family housing was added, until by the 1930 census, 15 families lived in homes and only six workers lived at the boarding house (along with the family of the house manager). The rise of automobile travel and ownership helped make workers able to commute, and fewer needed a boarding house.

Life in the quarry village was marked by tight-knit isolation, at least until the days of widespread automobile travel and snowplows. Residents of the 1920s often took the train to Newberry, St. Ignace or Sault Ste. Marie to shop, see motion pictures or for quarry business. An auto mobile ride to Rexton, five miles away, was a major social event and often an adventure in a Ford Model T bouncing along a corduroy road through land that was wilderness only a generation or two ago.

Baseball and softball were popular pastimes in the 1920s and ‘30s, both in organized area leagues and pickup games on a ball diamond near the quarry. Water that collects in one area of the quarry every year froze in winter and provided an ice rink for skating parties that included bon fires. One resident years later recalled occasionally walking five miles to Rexton with her brother to play with friends in the early ‘30s, then walking five miles back, taking up an entire Saturday.

Village residents could buy groceries from a company store (on credit, deducted from paychecks). Some families living near the caves that were eventually quarried away used the entrances as refrigerators to store butter, milk and even homemade beer. Gardens were typical in summe; canned fruits and vegetables were common table fare. One or two residents raised chickens and sold eggs to their neighbors. Some hunted deer and several young men snared rabbits and trapped beaver in the nearby ponds and swamps.

Dances were a huge part of social life in the region throughout the quarry’s life. Newspapers carried dozens of small ads announcing Saturday night dances in communities all over the area. Some dances were held at the boarding house at Fiborn, which also served as the hub for other social activities. Traveling salesmen frequently came by, especially in conjunction with dances and other events, to demonstrate and pitch new products. Traveling ministers regularly performed church services, and the village schoolchildren sometimes performed musical shows at the boarding house.

The village emptied quickly after the quarry closed permanently in January 1936. The quarry's last superintendent, Lynn Brockway, oversaw removal of equipment, authorized and oversaw occasional quarrying operations for road projects including the Mackinac Bridge, and remained on the property until the mid-1940s. He also supervised Fiborn Limestone Co.'s Ozark quarry during many of these years.

Over the years, stone was quarried occasionally by contractors who brought in their own equipment, for use in seawalls, roads and other building projects. Area residents occasionally obtained a pickup truck full of gravel or other rock; others scavenged the area for bottles and other antiques left over from the village; still others visited the caves near the former quarry. Largely, the area remained deserted.

The Michigan Karst Conservancy purchased the property in 1987 and established the Fiborn Karst Preserve, managing it as a natural area open to the public under guidelines meant to prevent damage to natural features, vandalism and unsupervised, unsafe cave exploration. See the Fiborn Karst Preserve page for details.